Later, official documents mention a medical examination that revealed Ruth suffered lasting physical consequences and severe nervous sensitivity. Despite this violent past, the records show a slow recovery: James became a laborer and later a landowner, Mary worked tirelessly, and the children learned to read.

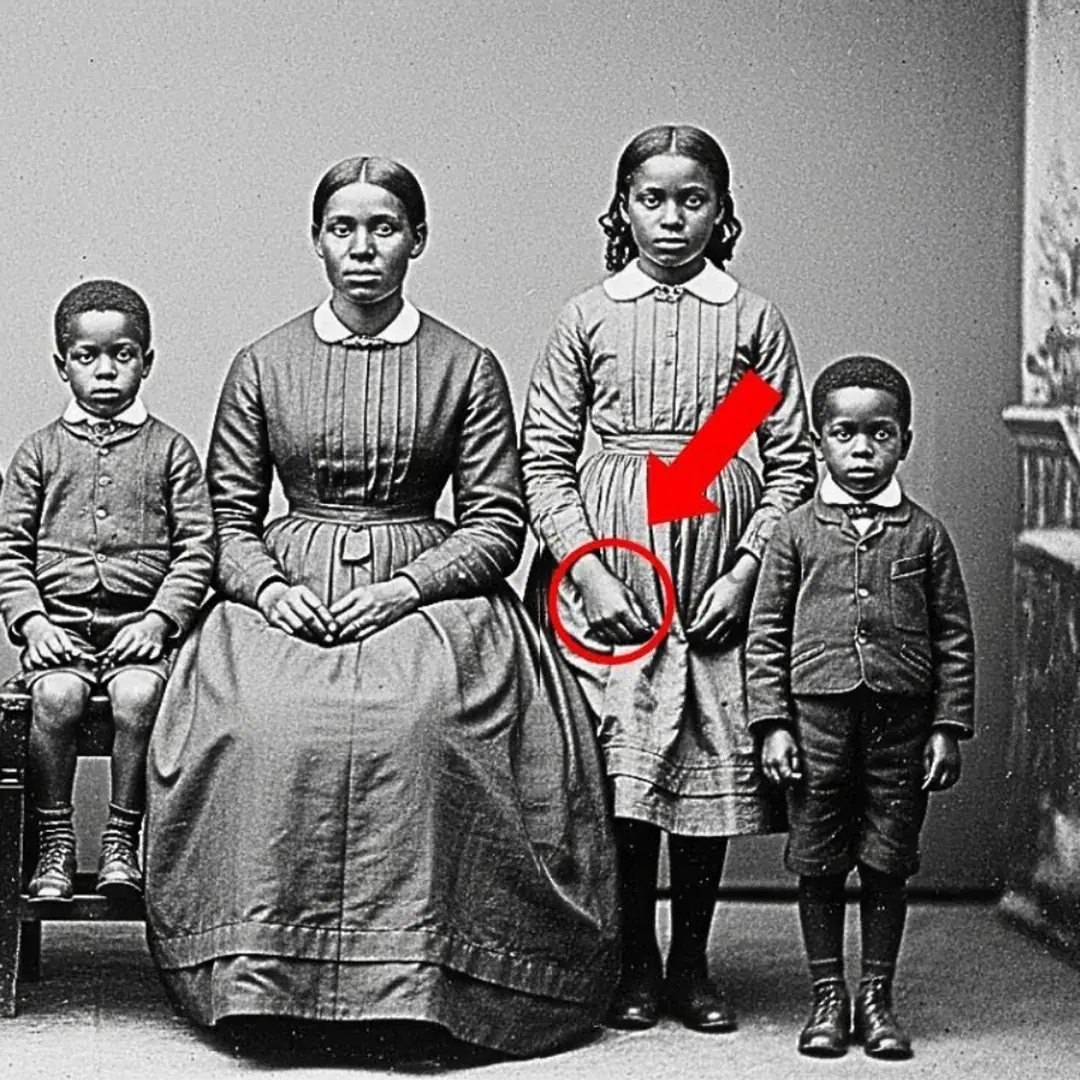

Decades later, Ruth wrote a few moving lines about her childhood and the photo shoot in a family Bible preserved by her descendants: Her father had insisted that they all be present and clearly visible because “this picture would last longer than their voices.”

When an anonymous family became a symbol:

Thanks to Sarah’s work and the testimony of a descendant of Ruth, the photograph finally emerges from anonymity. It becomes the centerpiece of the exhibition “The Washington Family: Survival, Reconstruction, Transmission,” a true collective African American memory.

This portrait from 1872 no longer simply depicts a family in their finest attire. It is proof that, after slavery, men, women, and children demanded the right to be perceived as a fully-fledged, dignified family, standing upright despite their scars.

Ruth’s hand, drawn but clearly visible, seems to say to those who look at it today: “We suffered, yes. But we also lived, loved, and built a future for ourselves. Don’t see us only as victims, but as survivors.”

And perhaps therein lies the most beautiful power of a simple old photograph: to transform repressed pain into a message of courage that lasts for generations.